|

MONDAY

15th APRIL 2003 (Day 1)

After

a disturbed night I was up at 04.30 to finish packing and to get

everything together ready for my departure. Carol rose at 05.00 and

after a quick breakfast she drove me to Smith's Coaches garage. There

the coach was waiting with Alan and Kath already aboard. They had taken

the front left seats so I sat immediately behind them. At 05.30 Brian,

our driver for the trip, headed into Marple. Soon we were standing by

the Regent Cinema and most of the rest of the party were boarding. Alan

and Kath were asked to move to the seats behind me so that Pete and Andy

could occupy the front ones with all their trip-running gear. I can

understand their desire to be at the front of the coach. Having

organised many similar trips I appreciate that the position near to the

driver at the front of the coach is the best from which to try to

control everything.

By

06.00 we were on our way and after picking up Jack at the Texaco garage

and a few more people in Offerton we made for the motorway. We had

another pickup at the Knutsford services before our final one at the

Stafford services, where we met Ray and his wife. Ray and I had shared a room

last year but this year his wife had come between us. Then it was full

tilt down the M6 into the first traffic jam. This was caused by what

proved to be an horrific accident involving a heavy goods vehicle. Its

cab was completely destroyed and several fire crews were hacking at the

debris, presumably to try to extricate the driver. I hope they were

successful. By

06.00 we were on our way and after picking up Jack at the Texaco garage

and a few more people in Offerton we made for the motorway. We had

another pickup at the Knutsford services before our final one at the

Stafford services, where we met Ray and his wife. Ray and I had shared a room

last year but this year his wife had come between us. Then it was full

tilt down the M6 into the first traffic jam. This was caused by what

proved to be an horrific accident involving a heavy goods vehicle. Its

cab was completely destroyed and several fire crews were hacking at the

debris, presumably to try to extricate the driver. I hope they were

successful.

Then

came Birmingham!!

It

was not until 09.30 that we reached Watford Gap services where we had

breakfast. We stopped for only thirty minutes during which I had a

horrid few rashers of soggy tasteless bacon between two slices of flabby

white sliced bread. With a pot of lukewarm coffee the bill was £5.38.

I've had a roast Sunday lunch in a pub for that sort of money - and

enjoyed eating it.

The

journey continued on around London. On the crest of the Queen Elizabeth

II bridge I was impressed by the fantastic scope of the view. What a

pity that the only things to see are part of a very unattractive

industrial landscape and the dirty river.

One

more stop and at 13.15 we were in the Eurotunnel terminal and driving on

to the train. This was my first journey under the English Channel and,

quite frankly, I wasn't looking forward to it. The train comprised

thirty units and we had the seventh one all to ourselves. Soon the

shutters between the units came down and we were sealed into the

compartment. For most of the trip we stood outside the coach as it was

too warm inside. The view from the compartment windows was,

understandably, not exciting. Thankfully the crossing took only a short

time and by 15.05 (local time) we were in France and heading northwards

towards Belgium

ARNEKE

CEMETERY

|

In

October 1917 the 13th Casualty Clearing Station moved back from

near Proven to Arneke and around it grew up the British

Cemetery. The 10th and 44th Clearing Stations joined it in April

1918. The cemetery was used by these hospitals until the end of

May and again from July to September 1918 by the 62nd (1/2

London) Clearing Station. In November the 4th and 10th

Stationary Hospitals used it for a short time. There are now

nearly 450 1914-18 and a small number of 1939-45 war casualties

commemorated in this site. |

The

first stop, at 16.30, was at Arneke military cemetery. It was a typical

Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery, situated down a narrow lane

and almost in the adjacent farmyard where Brian managed to turn the

coach around. As is usually the case the graves were enclosed by a small

wall. At the heart of the area is a white stone cross superimposed upon

which is a large bronze sword. Behind is the Stone of Remembrance

bearing the words 'THEIR NAMES LIVETH FOR EVERMORE'.

The

chief reason for visiting this particular site was for Frank to pay his

respects at the grave of an uncle, Private Joseph Cassidy of the Royal

Irish Fusiliers. He died at the age of 21 on 10th September 1918 of

wounds he had suffered at Messines. Arneke cemetery marks the site of a

casualty clearing station. This means that most of the graves are of soldiers who died there after they had been transported

from the front line. As a result, most if not all the headstones are able

to give the full details of the soldiers under them; their rank, name

and number, their regiment and the date on which they died. Often their

age is included and, at the bottom of the stone, a few lines are added by their

family. It also means that many different regiments and corps are

represented. There were also several French graves as a well as a few

German ones. Arneke cemetery is also the last resting-place of a Marple

man, F. S. Carter of the Cheshire Regiment. The

chief reason for visiting this particular site was for Frank to pay his

respects at the grave of an uncle, Private Joseph Cassidy of the Royal

Irish Fusiliers. He died at the age of 21 on 10th September 1918 of

wounds he had suffered at Messines. Arneke cemetery marks the site of a

casualty clearing station. This means that most of the graves are of soldiers who died there after they had been transported

from the front line. As a result, most if not all the headstones are able

to give the full details of the soldiers under them; their rank, name

and number, their regiment and the date on which they died. Often their

age is included and, at the bottom of the stone, a few lines are added by their

family. It also means that many different regiments and corps are

represented. There were also several French graves as a well as a few

German ones. Arneke cemetery is also the last resting-place of a Marple

man, F. S. Carter of the Cheshire Regiment.

On

the way to our next stop we passed close by the Mont des Cats. Andy

informed us that this is the very hill up which the Grand Old Duke of

York marched his 10,000 men before immediately marching them down again.

Generally this part of France/Belgium is very flat with only a few

small hills that dominate the surrounding countryside. It is easy to see

why the occupation of even such low hills became so vital to the

combatants of the Great War and, as we were to see, cost the lives of so

many men.

BAILLEUL

CEMETERY

|

Bailleul

was occupied on the 14th October 1914 by the 19th Brigade and

the 4th Division. It became an important railhead, air depot and

hospital centre; the 2nd, 3rd, 8th, 11th, 53rd, 1st Canadian and

1st Australian Casualty Clearing Stations were quartered in it

for considerable periods. It was a Corps Headquarters until July

1917 when it was severely bombed and shelled. The battle of

Bailleul, one of the Battles of the Lys, was fought between the

13th and 15th April 1918. The town was defended by the 29th,

31st, 34th and 59th (North Midland) Divisions and the 4th Guards

and 147th Brigades but it was entered by the Germans on the

evening of the 15th. By the end of the month the enemy advance

was held at St. Jans-Cappel and Meteren, north and west of

Bailleul, and the allied artillery had destroyed the town. It was

found empty and reoccupied on 30th August 1918.

There

are now nearly 4,500 1914-18 and a small number of 1939-45 war

casualties in this site. Of these nearly 200 from the 1914-18

War are unidentified and eleven special memorials record the

names of soldiers from the United Kingdom buried here in April

1918 whose graves were destroyed by shell fire. |

The

next cemetery, Bailleul, was between a housing estate and the local

civil graveyard. Again it marked the site of a casualty

clearing station and, being closer to the front, was larger than that at

Arneke. Once wounded, a soldier received initial basic treatment at the

regimental aid post before being passed back to the nearest dressing

station. Here an attempt would be made to stabilise the patient and make

him fit enough to be moved back to a casualty clearing station and

eventually, if he survived the journey, to a base hospital near the

Channel coast such as the one at Étaples that we visited last year.

Needless to say, many men did not complete this journey, made by any of

a variety of means of transport - motorised or horse-drawn ambulance,

train or canal barge. Their last resting places mark the smaller

clearing stations along the line of evacuation where they finally gave

up their sad struggle for life.

Bailleul

was also the scene of much hard fighting during the last German push and

its subsequent repulse in 1918. Some of the battle dead are buried in

this cemetery. For the first time on this trip we saw nameless graves,

their occupants 'KNOWN UNTO GOD'. The cemetery also contains some

unusual headstones. In among the usual British Army regiments we came

across the stones for men of the Indian Army who died so far from their

homeland in a cause they must have found difficult to understand. There

were Ghurkas and Pathans with their details recorded in strange scripts.

At the back of the cemetery was a row of stones marking the graves of

thirty members of the Chinese Labour Corps buried between November 1917

and March 1918. Bailleul

was also the scene of much hard fighting during the last German push and

its subsequent repulse in 1918. Some of the battle dead are buried in

this cemetery. For the first time on this trip we saw nameless graves,

their occupants 'KNOWN UNTO GOD'. The cemetery also contains some

unusual headstones. In among the usual British Army regiments we came

across the stones for men of the Indian Army who died so far from their

homeland in a cause they must have found difficult to understand. There

were Ghurkas and Pathans with their details recorded in strange scripts.

At the back of the cemetery was a row of stones marking the graves of

thirty members of the Chinese Labour Corps buried between November 1917

and March 1918.

We

had stopped here to visit the grave of Private John Cassidy, another of

Frank's uncles and older brother of Joseph Cassidy whom we had visited in

Arneke cemetery. John had also been in the Royal Irish Fusiliers but had

died of wounds on 17th November 1916. We wondered if, as he was

evacuated along the railway line, his younger brother had realised how

close he was passing to his already dead brother's grave.

Along

the edge of the cemetery were a number of German graves. A few of these

held men killed in 1944 when war once again passed through this part of

France.

At

18.15 we finally entered Belgium. A dilapidated border post, badly

decorated with graffiti, was the only indication of the transition from

one country to another. Soon we could see the spires of Ypres (or Ierper

as the local Flemish people prefer to know it) and the famous Cloth

Hall, all carefully reconstructed since 1918. It is hard to remember

that over 250,000 British troops died around here, representing one in

four of all the British dead for the whole of the war. Having rounded

Hellfire corner, allegedly the most shelled part of the whole front

line, we entered Ypres through the Menin Gate and eventually stopped

outside our hotel, the Ypres Novatel.

We

soon disembarked and Robin, my roommate for the week, and I headed for

our room. It came as some surprise to discover that the large and bright

room contained only one large double bed. We eventually became friends

but to start the friendship by sharing a bed was a big concept to grasp.

A quick visit back to Reception was enough to discover that the sofa

under the window was also a single bed so that solved that potential

problem.

THE

MENIN GATE AND "THE LAST POST" CEREMONY

|

The

original Menin Gate marked the start of one of the main roads

out of Ypres towards the front line. Tens of thousands of men

passed through it and along the infamous Menin Road. Too many of

them never returned. Then there was no actual gate and certainly

no arch. It was merely a gap in the town's ramparts with a

bridge across the moat.

Following

the end of the Great War, plans were discussed for a suitable

memorial in Ypres. The British Government suggested purchasing

the ruins of the town and leaving it as a memorial to the

soldiers and townspeople who had lost their lives in the

Salient. The Belgian Government refused to sanction this plan

but offered two possible sites in the town, the ruined Cloth

Hall or the Menin Gate. Following a change of heart over the

Cloth Hall it was decided to erect a memorial on the site of the

Menin Gate to those members of the British and Empire armies who

had died in the fighting around Ypres and who had no known

grave.

The

Gate was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and finally

completed, despite considerable construction difficulties, in

1927. It represents a great triumphal arch in the classical

Roman tradition. Made of French limestone and weighing 20,000

tons, the monument is 135 feet in length, 140 feet wide and 80

feet high. At the summit is a British Lion designed by Sir

William Reid Dick. It was intended to look "not fierce and

truculent, but patient and enduring, looking outward" along

the Menin Road. On great panels, all around the walls, are the

names of 54,896 officers and men of the Commonwealth forces.

This figure does not represent all the men who disappeared in

the Salient. It was discovered that the Menin Gate, huge as it

is, was not large enough to hold all the names of the missing.

The names recorded on its panels are of the men who died between

the outbreak of war in 1914 and 15th August 1917. The names of a

further 34,984 who went missing from then until the end of the

war are recorded on carved panels at Tyne Cot cemetery. The

Gate was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and finally

completed, despite considerable construction difficulties, in

1927. It represents a great triumphal arch in the classical

Roman tradition. Made of French limestone and weighing 20,000

tons, the monument is 135 feet in length, 140 feet wide and 80

feet high. At the summit is a British Lion designed by Sir

William Reid Dick. It was intended to look "not fierce and

truculent, but patient and enduring, looking outward" along

the Menin Road. On great panels, all around the walls, are the

names of 54,896 officers and men of the Commonwealth forces.

This figure does not represent all the men who disappeared in

the Salient. It was discovered that the Menin Gate, huge as it

is, was not large enough to hold all the names of the missing.

The names recorded on its panels are of the men who died between

the outbreak of war in 1914 and 15th August 1917. The names of a

further 34,984 who went missing from then until the end of the

war are recorded on carved panels at Tyne Cot cemetery.

Unveiling

the memorial on 24th July 1927 Field Marshal Plumer said: -

One

of the most tragic features of the Great War was the number of

casualties reported as missing, believed killed… When peace

came and the last ray of hope had been extinguished the void

seemed deeper and the outlook more forlorn for those who had no

grave to visit, no place where they could lay tokens of loving

remembrance…and it was resolved that here at Ypres, where so

many of the missing are known to have fallen, there should be

erected a memorial worthy of them which should give expression

to the nation's gratitude for their sacrifice and their sympathy

with those who mourned them. A memorial has been erected which,

in its simple grandeur, fulfils this object and now it can be

said of each one in whose honour we are assembled here today: He

is not missing; he is here! |

|

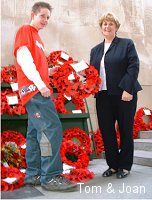

By

19.30 we were back down in the bar for a quick beer as the group

assembled. A quarter of an hour later we walked back to the Menin gate

to witness the regular evening ceremony of sounding the Last Post.

Tonight a crowd of about 200 people had congregated under the arch.

Sharp at 20.00, five smartly dressed firemen formed up across the road

and sounded the British Army's Last Post, the bugle call that

traditionally ends the day and is also sounded at military interments.

During the ensuing reverential silence various groups laid poppy wreaths

at the memorial. Tom and Joan, his grandmother, placed the one from the

Marple group. Finally the bugles sounded Reveille, the call that signals

the start of a new day.

THE

LAST POST

|

|

|

In

1928, a year after the inauguration of the Menin Gate Memorial,

a number of prominent citizens in Ypres decided that some way

should be found to express the gratitude of the Belgian nation

towards those who had died for its freedom and independence. The

idea of the daily sounding of the Last Post - the traditional

salute to the fallen warrior - was that of the Superintendent of

the Ypres police, Mr. P. Vandenbraambussche. The Menin Gate was

thought to be the most appropriate location for the ceremony.

The privilege of playing the Last Post was given to buglers of

the local volunteer Fire Brigade. In

1928, a year after the inauguration of the Menin Gate Memorial,

a number of prominent citizens in Ypres decided that some way

should be found to express the gratitude of the Belgian nation

towards those who had died for its freedom and independence. The

idea of the daily sounding of the Last Post - the traditional

salute to the fallen warrior - was that of the Superintendent of

the Ypres police, Mr. P. Vandenbraambussche. The Menin Gate was

thought to be the most appropriate location for the ceremony.

The privilege of playing the Last Post was given to buglers of

the local volunteer Fire Brigade.

The

first sounding of the Last Post took place on 1st July 1928 and

a daily ceremony was carried out for about four months. The

ceremony was reinstated in the Spring of 1929 and the Last Post

Committee was established. From 11th November 1929 the Last Post

has been sounded at the Menin Gate every night and in all

weathers. The only exception to this was during the four years

of the German occupation of Ypres from 20th May 1940 to 6th

September 1944. The daily ceremony was instead continued in

England at Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey. On the very

evening that Polish forces liberated Ypres the ceremony was

resumed at the Menin Gate in spite of the heavy fighting still

going on in other parts of the town. |

I

spent a few moments examining the names on the many marble panels that

cover every surface of the great construction. Every regiment and corps

in the British and Commonwealth armies is represented; men from the

English counties and towns, the Scottish Highlands and the Welsh

valleys, from Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and

India. It is almost too staggering to take in at one visit.

The

following Marple men are remembered on the walls of the Menin Gate (with

the date of their death): -

| Robert Ashton |

06/03/1915 |

| Francis Edmund

Bradshawe Isherwood |

09/05/1915 |

| Geoffrey

Hamilton Bagshawe |

13/05/1915 |

| Joseph Ardern |

20/06/1915 |

| Burt Morris |

07/06/1917 |

| John William

Hallworth |

13/06/1917 |

| Joseph Bell |

27/07/1917 |

| John William

Hayes |

31/07/1917* |

| Fred Hopwood |

31/07/1917* |

| Bertram Smith |

31/07/1917* |

| John Thomas

Booth |

31/07/1917* |

| Harold Matthew

Burton |

31/07/1917* |

| Robert Cunningham

Dixon |

31/07/1917* |

| James Everatt

Sharples |

03/08/1917 |

*

31st July 1917 was the start of the disastrous part of the Third Battle

of Ypres generally referred to as The Battle of Passchendaele.

After

the ceremony most of us repaired to a bar in the town square for a drink

and something to eat. I had steak with a mushroom sauce, which was very

tasty, with plenty of mushrooms. Those new to Belgium were fascinated by

the drinks menu with its long list of Belgian beers. Not everyone

realised that some of these beers are considerably stronger that our own

ales!

It

had been a long day and by the end of the meal I was feeling very tired.

Some of the party went off to another bar to continue the evening but I

crept back to the hotel and my bed.

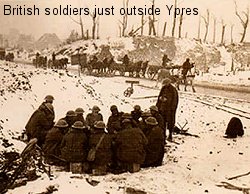

THE

FIRST BATTLE OF YPRES - OCTOBER TO NOVEMBER 1914

|

With

the failure of the German offensive against France at the battle

of the Marne and the allied counter-offensive, the so-called

Race to the Sea began, a movement towards the North Sea coast as

each army attempted to out-flank the other by moving

progressively north and west. As they went, each army

constructed a series of trench lines that came to characterise

the war on the Western front until 1918.

Meanwhile

on 14th September the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre,

undertook an intensive combined allied attack against the German

forces on the high ground just north of the Aisne River. The

German defences were too strong and the attack was called off on

18th September. Stalemate had set in.

By

October the Allies had reached the North Sea at Niuwpoort in

Belgium. German forces had driven the Belgian army out of

Antwerp and back towards Ypres. The British Expeditionary Force

(BEF) under Sir John French took over the line from Ypres south

to La Bassée in France from which point the French Army

continued the line down to the Swiss Border. Such was the

background to the First Battle of Ypres that commenced on 14th

October 1914 when Eric von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of

Staff, sent his 4th and 6th Armies into Ypres. By

October the Allies had reached the North Sea at Niuwpoort in

Belgium. German forces had driven the Belgian army out of

Antwerp and back towards Ypres. The British Expeditionary Force

(BEF) under Sir John French took over the line from Ypres south

to La Bassée in France from which point the French Army

continued the line down to the Swiss Border. Such was the

background to the First Battle of Ypres that commenced on 14th

October 1914 when Eric von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of

Staff, sent his 4th and 6th Armies into Ypres.

The

battle began with a nine-day German offensive that was only

halted with the arrival of French reinforcements and the

deliberate flooding of the Belgian front. Belgian troops opened

the sluice gates of the dykes holding back the sea from the low

country. The flood encompassed the final ten miles of the

trenches in the far north and would later prove a hindrance to

the movement of allied troops. During the German attack British

troops held their positions, suffering heavy casualties, as did

the French forces guarding the north of the town.

The

second phase of the battle saw a counter-offensive launched by

General Foch on 20th October, ultimately without success. It was

ended on 28th October.

Next

von Falkenhayn renewed his offensive on 29th October, attacking

most heavily in the south and east, once again without decisive

success, although by 1st November they had taken Messines Ridge,

Wytschaete and Gheluvelt and had broken the Menin Road. It

seemed as though an allied defeat was imminent. However, the

arrival of French reinforcements saved the town, the British

were able to counter-attack and Gheluvelt was recaptured.

The

German offensive continued for the following ten days, the fate

of Ypres still in the balance. A further injection of French

reinforcements arrived on 4th November. Even so, evacuation of

the town seemed likely on 9th November as the German forces

pressed home their attack, taking St. Eloi on 10th November and

pouring everything into an attempt to recapture Gheluvelt on

11th and 12th November, but without success. A final major German

assault was launched on 15th November. Still Ypres held out. Now

the Belgian autumn had set in and soon heavy rain arrived

followed by snow. Von Falkenhayn called off his attack. The

German offensive continued for the following ten days, the fate

of Ypres still in the balance. A further injection of French

reinforcements arrived on 4th November. Even so, evacuation of

the town seemed likely on 9th November as the German forces

pressed home their attack, taking St. Eloi on 10th November and

pouring everything into an attempt to recapture Gheluvelt on

11th and 12th November, but without success. A final major German

assault was launched on 15th November. Still Ypres held out. Now

the Belgian autumn had set in and soon heavy rain arrived

followed by snow. Von Falkenhayn called off his attack.

It

was becoming evident that the nature of trench warfare favoured

the defender rather than the attacker. The BEF had held Ypres as

they continued to do until the end of the war despite repeated

German assaults. The Allies now held a salient extending six

miles into the German lines. The cost had been huge on both

sides. British casualties were 58,155, mostly from the pre-war

professional army - the last of the Old Contemptibles. French

casualties were around 50,000 and Germany lost 130,000 soldiers. |

|